Minu koolitee algas 1. septembril 1992 Haapsalu 1. Keskkoolis. Kuna suurem osa minu õppetööst möödus laua all autodega mängides ning lihtsalt olles — ja vahel ka Tootsi moodi köstri eest mööda lauaaluseid põgenedes — suunati mind 1. septembril 1993 Haapsalu Sanatoorsesse Internaatkooli. Vanemad, ja ilmselt ka õpetajad, kahtlustasid, et sünnist saadik saadud narkoosikogused, mis olid seotud minu operatsioonidega, olid mu mõistust kahjustanud.

Haapsalu Sanatoorses Internaatkoolis selgus üsna pea tõsiasi, et poiss on ju ikkagi esimeses klassis juba käinud – sest ta täitis kättesaadud töövihikud kiiremini ära, kui esimene veerand kooliaastast läbi sai. Samuti luges soravalt, kui teised alles tähti õppisid. Ilmselt tegelesin ka laua all mängides tahestahtmata õppetööga, ja samuti kodus laineliseks nutetud AABITS oli minu viis teadmiste omandamiseks – kuid see ei olnud aktsepteeritav äsja Nõukogude Liidust vabanenud Eesti Vabariigi haridussüsteemile. Toonane mõttelaad, et erinevus rikastab, oli taunitav ning õpetajatele vastuvõetamatu.

Paraku just Haapsalu Sanatoorne Internaatkool (HSIK) oligi suunatud oma õppemetoodikaga inimeste erinevustele. Selle tõttu omandasid ka need lapsed teadmised, mida tavakool ei suvatsenudki anda. Egas tavakool polekski saanud endale lubada mõnda lauaalust mässajat, kes oleks võinud teisedki klassi lapsed mõtlema panna – miks tema võib, aga meie mitte?

Poole aasta pealt tegi HSIK klassijuhataja vanematele ettepaneku poiss viia edasi teise klassi, kuna tema teadmised olid selle väärilised. Paraku otsustajaks sai minu vanaema Magda, kes ütles, et poiss on õpetaja ja klassikaaslastega harjunud ning koolis käia on aega küll. Selle tõttu jäingi “istuma” esimesse klassi. Tagantjärele mõeldes on see ikka naljakas – nagu mingis anekdoodis.

Mis mulle enim HSIK juures meeldis, oli see, et õppejõud tegelesid iga lapsega personaalselt, just tema isikuomadustele vastavalt ja tema võimete piires. Lapsi ei jäetud ka oma päi peale tunde – seal võtsid lastega tegelemise üle kasvatajad erinevate huviringidega. Tänapäeval on internaatkoolid hädas, et lapsed tegelevad lollustega pärast koolitööd, kuid just seal peitubki eduvõti. HSIK-s lastel ei jäänudki aega lollusteks, sest nende vaba aeg planeeriti ära kasvatajate poolt. Loomulikult esines ka juhuseid, kus “siga leidis pori”, kuid see polnud igapäevane, vaid pigem harv juhus.

Olen väga tänulik kõigile pedagoogidele, kellega nende 10 aasta jooksul koostööd sai tehtud. Jah, just koostööd, sest minu õpetamise ja lahenduste leidmisega õppisid lisaks minule ka õpetajad. Seda nimetame hellitavalt kogemusteks, mis omakorda tuli kasuks tulevikus.

Hei õps, vaata siia, spikker!!!

Kui nüüd analüüsida minu massilist spikerdamist paljudes tundides, siis see oli ilmselgelt põhjustatud sellest, et ma ei näinud mõtet teadmistel, mida ma eeldatavasti elus kunagi ei kasuta. Aga nagu klassikud ütlevad: “Ära iial ütle iial!”. Samuti keeldus mu aju mõnel juhul koostööst, kui asjad muutusid liiga keeruliseks.

Saksa keele õpetaja Tiiu Sein oli mulle üks armastatud, kuid samas ka mitte sallitud õpetajaid – sest ta oli väga range ja andis pidevalt pähe õppida. Samas oli tema inimlik pool äge ja väga armastatud. Ilmselt olin spikri tegemisel, mille ta minult lõpuks konfiskeeris, arvestanud ka vahele jäämisega – sellest tulenebki see hüüdlause. Eks elus ongi ju vajalik alati arvestada vastutusega, mis on tingitud sinu tegevusest. Oma asi on nüüd see, kas ma lootsin, et jään vahele või mitte. Üldjuhul olid spikerdamise abil saadud head hinded mulle motivatsiooniks, ja võisin olla uhke, et oskan spikerdada.

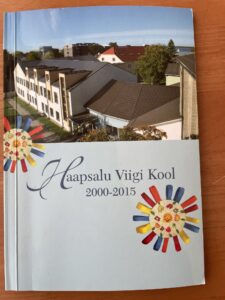

Kokkuvõtlikult: üritus Viigi koolis oli tore. Taaskohtumine endiste õpetajate, kasvatajate ja koolikaaslastega oli nostalgiline. Aktus oli toredalt läbi mõeldud ja kogu koolipere taas kaasatud – nagu vanadel headel aegadel.

Olgugi, et Haridusministeeriumi lubadused olid kooli saalis positiivsed, on minevikus olnud õhus kooli sulgemise teema, mida võtan väga isiklikult. Kuna minu meeskond omab rahvusvahelist mõju nii poliitikas kui ka meedias, siis hoian meie kooli käekäigul silma peal. Südamest loodan, et minu kõrvu ei peaks enam kunagi jõudma sõnumeid, kus räägitakse Haapsalu Viigi Kooli sulgemisest.

Olen palju kritiseerinud meie praegust haridussüsteemi ja ülikoole, nende 150 soo ja “Woke” agendaga. Võin julgelt täna öelda, et tegelik päris ülikool seisneb teadmiste ja oskuste andmises ning omandamises – mitte ideoloogiliste väärtuste programmeerimises. Selleks võin julgelt öelda, et Haapsalu Sanatoorse Internaatkooli näol olen ma samuti tegelikult ka “ülikooli” läbi teinud.

/Mario Maripuu, eestieest.com toimetaja, kolumnist ja saatejuht/

***

My school journey began on September 1st, 1992, at Haapsalu 1st Secondary School. Since most of my study time was spent playing with toy cars under the desk — simply existing, and occasionally fleeing under the desks like Toots from the parish clerk — I was directed on September 1st, 1993, to Haapsalu Sanatorium Boarding School. My parents, and probably the teachers too, suspected that the amounts of anesthesia I had received since birth during my surgeries had affected my brain.

At Haapsalu Sanatorium Boarding School (HSIK), it became quickly evident that the boy had already been to first grade — he was finishing his workbooks faster than the first quarter of the school year had passed. He also read fluently while others were still learning the alphabet. Apparently, even under the desk, I was inadvertently participating in class, and the ABC book at home — crinkled from crying — was my way of acquiring knowledge. But this wasn’t acceptable in the education system of the newly independent Republic of Estonia. At the time, the mindset was that “diversity enriches” — but that was frowned upon and unacceptable to the teachers.

Ironically, HSIK was precisely the kind of school that embraced people’s differences in its teaching methods. Because of this, even those children gained knowledge that regular schools weren’t willing to offer. A regular school could never afford to have a little rebel under the desk who might make the other kids start wondering — why can he, but we can’t?

Halfway through the year, my HSIK homeroom teacher suggested to my parents that I should be moved up to second grade, as my knowledge was already at that level. But the final decision came from my grandmother, Magda, who said that the boy had already bonded with the teacher and classmates, and there’s plenty of time to go to school. So, I stayed “back” in first grade. Looking back, it’s actually pretty funny — like something out of a joke.

What I liked most about HSIK was that the educators worked with each child personally, according to their character and abilities. Children weren’t left to their own devices after class — caregivers took over with various hobby groups. Nowadays, boarding schools struggle because kids get up to mischief after schoolwork, but therein lies the key to success. At HSIK, the children simply didn’t have time for nonsense, because their free time was scheduled by the caregivers. Of course, there were occasions when “the pig found the mud,” but those were rare, not everyday occurrences.

I’m deeply grateful to all the educators I worked with during those ten years. Yes, “worked with” — because as they taught me and looked for solutions, the teachers were learning too. We call that experience — something that benefits everyone later in life.

Hey teacher, look here — cheat sheet!!!

If I analyze my frequent cheating in many classes, it was clearly due to the fact that I didn’t see any point in knowledge that I assumed I’d never use in life. But as the classics say: “Never say never!” Also, my brain sometimes simply refused to cooperate when things got too complicated.

My German teacher, Tiiu Sein, was one of those teachers I both loved and couldn’t stand — because she was strict and always gave us material to memorize. But her human side was awesome and very much loved. I probably expected to get caught when she finally confiscated one of my cheat sheets — hence that shout. In life, it’s always necessary to take responsibility for your actions. Whether I wanted to get caught or not, who knows. Usually, the good grades earned from cheating gave me motivation, and I could even be proud that I was good at it.

In summary: The event at Viigi School was wonderful. Reuniting with former teachers, caregivers, and classmates was nostalgic. The ceremony was thoughtfully organized, and the whole school community was involved — just like the good old days.

Even though the Ministry of Education’s promises were positive during the ceremony, the topic of closing the school has surfaced in the past — and I take that very personally. Since my team has international influence in both politics and media, I will be keeping a close eye on the school’s future. I sincerely hope I’ll never again hear talk of Haapsalu Viigi School being closed.

I have often criticized our current education system and universities, with their 150 genders and “woke” agenda. I can proudly say that real university is about acquiring knowledge and skills — not programming ideological values. That’s why I can confidently say: in many ways, Haapsalu Sanatorium Boarding School was also a real “university” for me.

/Mario Maripuu, editor, columnist, and host at eestieest.com/